Explore The Church

AN 18th CENTURY REFUGEE

He lies in an unmarked grave somewhere in the parish churchyard, buried on Friday 15th April 1796, age 38. The burial record is brief and to the point: “Jean Glemée, Prêtre émigré, vicaire de la paroisse de Plélan, Diocese de St. Malo.” Who was he? How did a French Catholic priest come to be buried in St Clement? The answer goes back to a nearly-forgotten time when Jersey reeled under the pressure of unprecedented numbers of refugees. Not so long ago we witnessed extraordinary events as refugees fled to Europe from persecution in the Middle East but events in Jersey in the 1790s were every bit as extraordinary. The French Revolution (1787-1799) resulted in huge numbers of refugees fleeing the country. Jersey had little more than 20,000 inhabitants at the time but in the space of a few months between 3,000-4,000 arrived in the island, equivalent to 16-20% of the population. Those numbers are equivalent to England or France having to deal with 10-12 million refugees today.

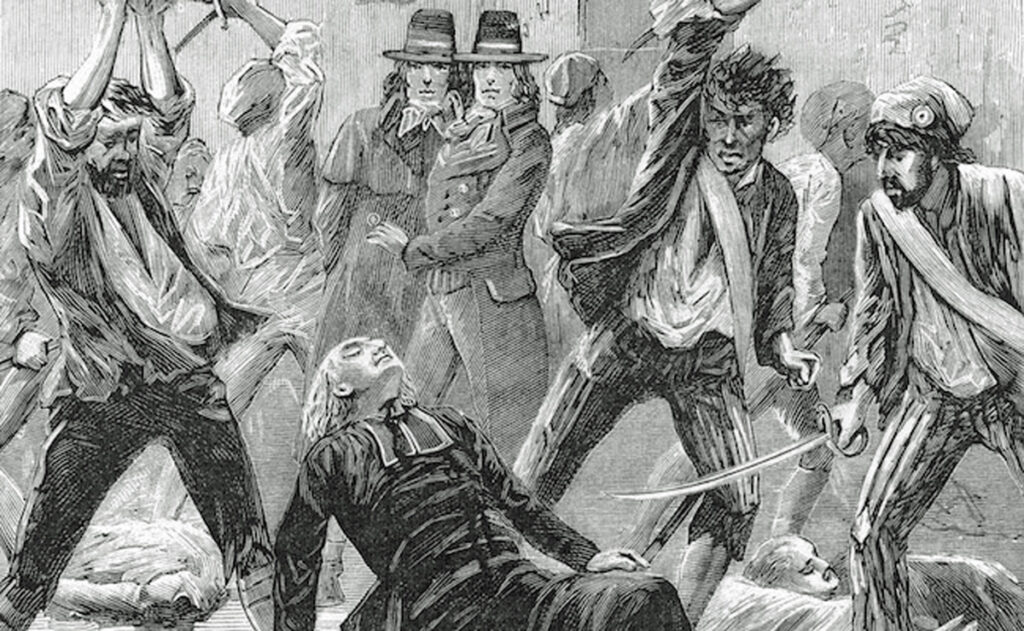

The refugees consisted of two main groups: nobles and their families, and so-called “refractory” priests, who had refused to swear loyalty to the new Republic and become state employees under the Civil Constitution of Clergy (12th July 1790). The priests who refused to fall into line were either expelled or killed. It is estimated that in 1792 around 1,800 sought refuge in Jersey in response to calls from the bishops of Bayeux, Tréguier and Dol. To put that number into context, there are around 1,000 pupils at Le Rocquier School today.

Jean Glemée was one of these refugee priests. Immediately prior to the Revolution he was vicaire (curate, or assistant priest) in the parish of Plélan-le-Petit, a small town situated just over 16km west of Dinan, along with Père Le Gallais, who was prieur (rector). We know from Plélan’s baptism and marriage registers that they continued to carry out their ministry until October 1792, two years after the Civil Constitution of Clergy was enacted. They both fled before 23rd December in that year (the day on which a State Priest by the name of Marc Haye was installed), Père Le Gallais to England and Père Glemée to St Clément.

The arrival of large numbers of people in Jersey had significant consequences for the local economy: trade with England underwent an unprecedented boom along with the construction industry, as all these people had to be housed. The influx of the French refugees led to the expansion of St Helier because, having no particular connection with the country parishes, they preferred to stick together in the island’s capital. However, some did settle along the south coast: in First Tower; Millbrook; Beaumont and St Aubin, and also out to the east in Gorey. Plélan-le-Petit was an empty agricultural parish; something about the St Clément of the 1790s must have reminded Jean Glemée of home.

Imagine the reaction to a 16-20% jump in population in a couple of months today! It is understandable why in the mid-1790s the States of Jersey debated the expulsion of the refugees on the grounds that they were causing a disturbance in island life. We do not know whether any voices were raised in opposition to this move on humanitarian grounds: sending nobles, their families and prêtres réfractaires back to Revolutionary France would have surely condemned them to death. The argument that was advanced (and which prevailed) came from a rather surprising direction: the Jersey Chamber of Commerce opposed the measure citing the positive effect that the French refugees were having on the local economy. They were creating employment for many poor people which had in turn led to salaries rising faster than prices. It had also had the effect of reducing the cost of administering the “parish relief”, which meant lower rates for parishioners.

Jean Glemée died a young man but his many compatriots would go on to greatly contribute to island life. Their legacy is to be found in the French surnames of many island people to this day. Are we right to talk of “the refugee problem” in our time?